Function And Structure Of The Digestive System – The function of the digestive system is to break down the foods you eat, release their nutrients, and absorb those nutrients into the body. Although the small intestine is the workhorse of the system, where most digestion takes place and where most of the released nutrients are absorbed into the blood or lymph, each of the organs of the digestive system makes a vital contribution to this process.

As is the case with all body systems, the digestive system does not work in isolation; it works in cooperation with other body systems. Consider, for example, the relationship between the digestive and cardiovascular systems. Arteries supply the digestive organs with oxygen and processed nutrients, and veins drain the digestive tract. These intestinal veins, which make up the hepatic portal system, are unique; they do not return blood directly to the heart. Instead, this blood is diverted to the liver, where its nutrients are unloaded for processing before the blood completes its circuit back to the heart. At the same time, the digestive system provides nutrients to the heart muscle and vascular tissue to support their function. The interrelationship of the digestive and endocrine systems is also critical. Hormones secreted by several endocrine glands, as well as endocrine cells of the pancreas, stomach, and small intestine, contribute to the control of digestion and metabolism of nutrients. In turn, the digestive system provides the nutrients to fuel endocrine function. Table 1 provides a quick overview of how these other systems contribute to the functioning of the digestive system.

Function And Structure Of The Digestive System

Lymphoid tissues associated with mucosa and other lymphatic tissues protect against the entry of pathogens; lacteals absorb lipids; and lymphatic vessels transport lipids into the bloodstream

Digestive System Processes And Regulation

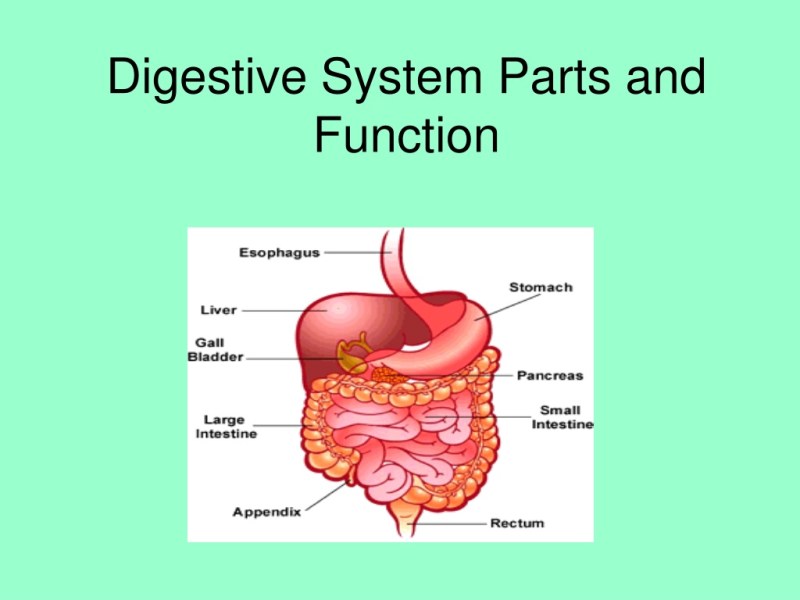

The easiest way to understand the digestive system is to divide its organs into two main categories. The first group are the organs that make up the alimentary canal. The digestive organs make up the second group and are critical for orchestrating the breakdown of food and assimilation of its nutrients in the body. Digestive organs, regardless of their name, are critical to the function of the digestive system.

Also called the gastrointestinal (GI) tract or intestine, the alimentary canal (aliment- = “to feed”) is a unidirectional tube about 7.62 meters (25 feet) long in life and closer to 10.67 meters (35 feet) in length when measured postmortem, as smooth muscle tone is lost. The main function of the organs of the digestive tract is to nourish the body. This tube starts at the mouth and ends at the anus. Between these two points, the canal is modified as the pharynx, esophagus, stomach, and small and large intestines to suit the functional needs of the body. Both the mouth and the anus are open to the external environment; Thus, food and waste within the alimentary canal are technically considered to be outside the body. It is only through the process of absorption that the nutrients in food enter and nourish the “inner space” of the body.

Each accessory digestive organ helps break down food. Inside the mouth, the teeth and tongue initiate mechanical digestion, while the salivary glands initiate chemical digestion. Once food products enter the small intestine, the gallbladder, liver, and pancreas release secretions—such as bile and enzymes—essential to continuing digestion. Together, these are called accessory organs because they sprout from the inner cells of the developing gut (mucosa) and add to its function; indeed, you cannot live without their vital contributions, and many important diseases result from their dysfunction. Even after development is complete, they maintain a connection with the intestines by means of ducts.

Throughout its length, the alimentary tract is composed of the same four tissue layers; the details of their structural arrangements vary to suit their specific functions. Starting from the lumen and moving outward, these layers are mucosa, submucosa, muscularis, and serosa, which is continuous with the mesentery.

Overview Of The Digestive System

Figure 2. The alimentary canal wall has four basic tissue layers: mucosa, submucosa, muscularis, and serosa.

The mucosa is called a mucous membrane because the production of mucus is a characteristic feature of the intestinal epithelium. The membrane consists of the epithelium, which is in direct contact with ingested food, and the lamina propria, a layer of connective tissue analogous to the dermis. In addition, the mucosa has a thin layer of smooth muscle, called the muscularis mucosa (not to be confused with the muscular layer, described below).

As its name implies, the submucosa lies immediately below the mucosa. A broad layer of dense connective tissue, it connects the overlying mucosa to the underlying muscularis. It includes blood and lymphatic vessels (which transport absorbed nutrients) and a distribution of submucosal glands that release digestive secretions. In addition, it serves as a conduit for a dense branching network of nerves, the submucosal plexus, which functions as described below.

The third layer of the alimentary canal is the muscularis (also called muscularis externa). The muscularis in the small intestine consists of a double layer of smooth muscle: an inner circular layer and an outer longitudinal layer. Contractions of these layers promote mechanical digestion, expose more food to digestive chemicals, and move food along the canal. In the more proximal and distal regions of the alimentary canal, including the mouth, pharynx, anterior esophagus, and external anal sphincter, the musculature consists of skeletal muscle, which gives you voluntary control over swallowing and defecation. The basic two-layered structure found in the small intestine is modified in organs proximal and distal to it. The stomach is equipped for its shocking function by adding a third layer, the oblique muscle. While the large intestine has two layers like the small intestine, its longitudinal layer is divided into three narrow parallel bands, the tenia coli, which make it look like a series of pouches rather than a simple tube.

The Human Digestive System (2.1.3)

The serosa is the part of the superficial to muscular alimentary canal. Present only in the region of the alimentary canal within the abdominal cavity, it consists of a layer of visceral peritoneum covering a layer of loose connective tissue. Instead of serosa, the mouth, pharynx, and esophagus have a dense layer of collagen fibers called the adventitia. These tissues serve to hold the alimentary canal in place near the ventral surface of the vertebral column.

As soon as food enters the mouth, it is detected by receptors that send impulses along the sensory neurons of the cranial nerves. Without these nerves, not only would your food be tasteless, but you also wouldn’t be able to feel either the food or the structures in your mouth, and you wouldn’t be able to avoid biting yourself while chewing, a motor-powered action . branches of cranial nerves.

The internal innervation of most of the alimentary canal is provided by the enteric nervous system, which runs from the esophagus to the anus and contains approximately 100 million motor, sensory, and interneurons (unique to this system compared to all other parts of the alimentary canal). peripheral nervous system). These enteric neurons are grouped into two plexuses. The myenteric plexus (Auerbach’s plexus) lies in the muscular layer of the alimentary canal and is responsible for motility, especially the rhythm and force of muscle contractions. The submucosal plexus (plexus of Meissner) lies in the submucosal layer and is responsible for the regulation of digestive secretions and the response to the presence of food.

The external innervations of the alimentary canal are provided by the autonomic nervous system, which includes the sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves. In general, sympathetic activation (the fight-or-flight response) limits the activity of enteric neurons, thereby decreasing secretion and GI motility. In contrast, parasympathetic activation (rest and digest response) increases GI secretion and motility by stimulating neurons of the enteric nervous system.

Protein Digestion And Absorption

The blood vessels that serve the digestive system have two functions. They transport protein and carbohydrate nutrients absorbed by the mucosal cells after the food is digested in the lumen. Lipids are absorbed through lacteals, small structures of the lymphatic system. The second function of blood vessels is to supply the organs of the alimentary canal with the nutrients and oxygen necessary to run their cellular processes.

In particular, the most anterior parts of the alimentary canal are supplied with blood from the arteries that branch off from the aortic arch and the thoracic aorta. Below this point, the alimentary canal is supplied with blood by arteries that branch off from the abdominal aorta. The celiac trunk serves the liver, stomach, and duodenum, while the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries supply blood to the remaining small and large intestines.

Veins that collect nutrient-rich blood from the small intestine (where most absorption occurs) empty into the hepatic portal system. This venous network carries blood to the liver, where nutrients are either processed or stored for later use. Only then does the blood flowing from the internal organs of the digestive tract circulate back to the heart. To appreciate how demanding the digestive process is on the cardiovascular system, consider that while you’re “resting and digesting,” about a quarter of the blood pumped with each heartbeat enters the arteries serving the intestines.

Digestive organs inside

Large Intestine Function

The digestive system structure and function, structure and function of the immune system, structure and function of the digestive system, parts of digestive system and its function, structure and function of the musculoskeletal system, the structure of digestive system, digestive system structure and function table, function and structure of the nervous system, structure and function of the endocrine system, function of the digestive system, parts and function of the digestive system, digestive system structure and function chart